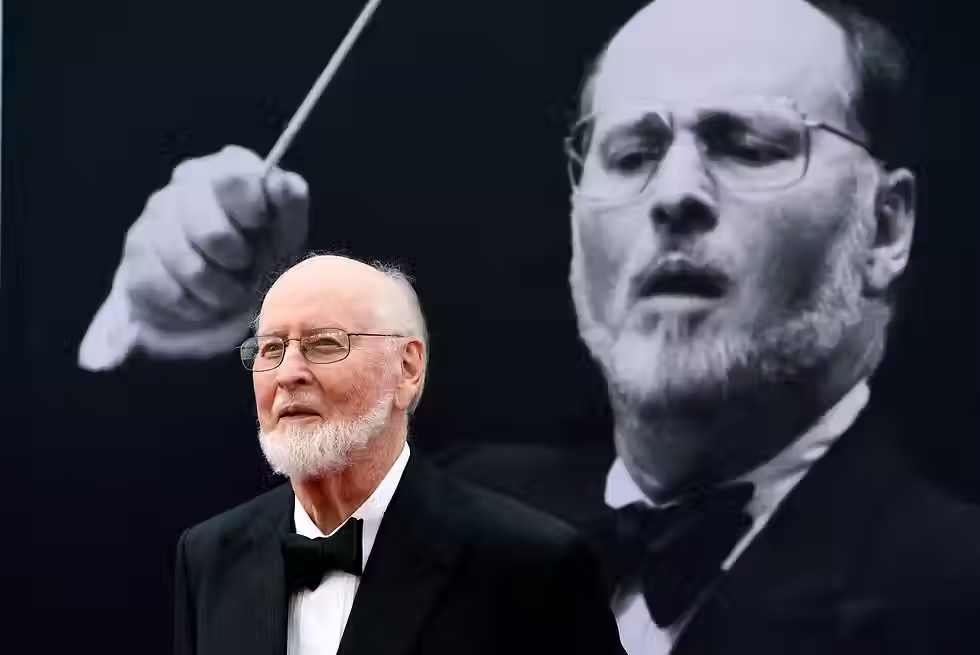

John Williams: A Composer’s Life by Tim Greiving

- South West Silents

- Aug 19, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2025

Co-director of South West Silents James Harrison explores the brand new biography about film composer John Williams by Tim Greiving and published by Oxford University Press.

Many have been longing to have an extensive biography about John Williams. Yes, there has been articles, the odd book has appeared over the years as well as press interviews. The recent Disney+ ‘Music by John Williams’ (2024) documentary has shined some light on William’s life and work, and yet it seemed rather lite at points. All this coverage is for good reason of course. After all, John Williams’ entire discography/filmography is very much the soundtrack to many a cinemagoing experience for over half a century.

But Tim Greiving’s new biography John Williams: A Composer’s Life (which hits 640 pages) brings more to the table than anything else that has come before. This isn’t just a standard music/film composer biography. It is thoroughly researched and Greiving has been able to enhance every piece of work which Williams has encountered in his career. The book includes key insights into how such a piece of music came about and the impact that music makes whether in a concert hall or on the screen. And the key thing here is, John Williams collaborated with Greiving on the book!

Given that so much has been covered before, is there anything new to say? Well, yes, and there is still a lot to learn from this new biography. There is those classic, well established, anecdotes set around scores such as Jaws (1975) (Spielberg initially laughing at the theme when played on the piano) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) (the idea of combing two initial melodies to make The Raiders March) to name a few.

But I for one, never knew the connection between to Star Wars: Episode I: The Phantom Menace’s (1999) Dual of the Fates theme and the Welsh language. And with hindsight, I probably should have known about it, being Welsh after all and being a fan of Williams’ music. And that’s the great thing with great biographies, you never know what you are about to learn. And I learnt a lot from John Williams: A Composer’s Life.

Williams’ early work is thoroughly studied as well, especially his jazz work and the impact it had on future television projects such as M Squad (1957-1960) and Checkmate (1960–1962) as well as future film work including William Wyler's How to Steal a Million (1966), Fiddler on the Roof (1971), Robert Altman's Images (1972) and his neo-noir The Long Goodbye (1973).

Then there is Williams’ encounters with other composers and their work for television and film in Hollywood. One day Williams is playing the piano riff for Henry Mancini’s theme for the Peter Gunn (1958-1961) series and then the next day Williams’ finds himself playing on film session recordings for the likes of West Side Story (1961), The Big Country (1958), Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1960) and Don Siegel’s noir The Killer’s (1964). Williams’ work and achievements are endless and having Tim Greiving guide us through his work is just wonderful.

So much of Williams’ work is so well catalogued here you just wonder what life John Williams has outside of his work. In fact, before I started reading this biography, I realised I knew really nothing about the life of John Williams the man. Williams’ personal life is very much a private one, so when it comes to a biography, it is a fundamental element; of course it is. And therein lies the problem with such a project.

In his acknowledgements, Greiving opens with the line ‘John Williams did not want me to write this book’. But this isn’t the first time such issues have occurred before. After all, David Lean wasn’t interested in having a biography written about him; that changed after he met author and historian Kevin Brownlow (Kevin should have is own written biography by the way). The same issue appeared with Alessandro De Rosa when it came to Ennio Morricone; thankfully, once again, an authorised biography was published.

However, Tim Greiving explains the many issues which he encountered to even indicate his plans, let alone speak to Williams. All doors were closed very firmly and very quickly when he approached his office. While making documentaries for the BBC I have been in the same situation, not with John Williams specifically, but most certainly with members within the same circle of collaborators. Emails and phone calls are made from Hollywood offices and suddenly those circled wagons appear. To be on the receiving end of this is heart-breaking. Contacts you originally had, no longer want to reply or return your calls because they have been told not to speak to you.

And to be honest, it is understandable at points, given the many requests and projects which are usually banging on doors for some sort of collaboration. But, it is a very lonely place to be. There is also the private life of a subject and what kind of ‘biography’ is such an author planning to write. And, as I have hopefully illustrated above, Greiving was planning to write the ‘right’ kind of biography. The acknowledgement chapter is an incredible insight on how these things work out; it is rather gut-wrenching at times.

And whoever or whatever changed John Williams’ mind to collaborate with Tim Greiving in the end, after many months of hard work, then we have to be grateful. As John Williams: A Composer’s Life is an important document of cinema and music history. It showcases his work with Williams’ own insights and emotional connections to pieces of work that has never been discussed or mentioned before.

Greiving also highlights the impact of the music alone on audiences, filmmakers, fellow composers (André Previn’s thoughts are pretty eye opening) and critics. Incredibly, some of the most celebrated of Williams' works did receive negative comments where the critic’s tastes, let alone their insanity, should really be questioned. And maybe this has impacted on Williams’ own take on his own work.

I do hope Williams knows how fundamental his work is not only on the history of cinema but on the history of music overall. Culturally, the impact on John Williams' work is up there with Mozart, Beethoven, Stravinsky, Gershwin and Shostakovich. I’m sure Williams does know how important and how much love there is out there for him and his work… like I said… I hope he does.

It is at this point I should add that John Williams: A Composer’s Life most certainly can sit alongside other recent key film composer biographies as well, Steven C. Smith’s (who gets a mention in the Williams book) excellent Music by Max Steiner and Alessandro De Rosa’s eye opening, Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words. Worth noting that both titles are also published by Oxford University Press.

So, get yourself a copy of Tim Greiving’s John Williams: A Composer’s Life, get your John Williams albums out and play them loud. You won’t regret it.

Comments